Photographer Captures Portraits of ‘Grandma Divers’ Who Free Dive Deep Into the Sea [Interview]

A group of women in the Korean province of Jeju dives deep beneath the water to collect seafood and other aquatic treasures. Known as Haenyeo (meaning “sea women”) they are part of a tradition that dates back to 434 CE. But they aren’t young people, as you might expect from a group who routinely conquers depths between 32 and 65 feet and can hold their breath for up to two minutes. The Haenyeo are mostly over the age of 60.

Photographer Alain Schroder spent time with the women and introduces them to a broader audience in his series Grandma Divers. He first visited Jejudo Island in 2019, where he witnessed the divers gathering mollusks, seaweed, and more. They came out of the water with the backdrop of basalt (volcanic) rock, and he began photographing them using a telephoto lens. Captivated, Schroder knew he needed to go back to shoot a dedicated portrait series.

Schroder returned that September with an interpreter and was ready to shoot. The weather conditions weren’t ideal, and, at first, the Haenyeo were less than enthusiastic about him being there. Despite these challenges, the compelling portrait series is a striking look at the women who are treasured part of South Korean society and singlehandedly keep the freediving tradition alive.

We spoke with Schroder about Grandma Divers, how it came together, and the history behind the incredible Haenyeo. Scroll down for My Modern Met’s exclusive interview.

Photographer Alain Schroder captures the women carrying on the Korean tradition of freediving in his series Grandma Divers. Learn more about it in My Modern Met's exclusive interview, below.

How did you get your start in photography?

How did you get your start in photography?

When I was 16–17, I was studying fine arts, and I spent a lot of time at the library reading fine art books. When I had seen everything they had about painting, the librarian gave me some photography books. One was the famous French magazine PHOTO, and the first story I liked and remember was by a Japanese photographer, Kishin Shinoyama. It was a very interesting magazine as it mixed all kinds of photography—fashion, documentary, travel, war, and personal work—in one issue. After that, I discovered another famous magazine called ZOOM, and all the classic photographers like Cartier-Bresson, Koudelka… I was hooked and switched immediately from fine arts to photography.

As a student with very little money, I traveled to Afghanistan and caught the travel virus. It was the perfect combination of travel and photography but it wasn’t easy to make a living. Of course, you need a little bit of luck and that came by coincidence in the form of sports photography. I was asked to replace a tennis photographer who was sick. At first, I declined as I did not have the right (telephoto) lenses, but the magazine had its own equipment so I could not refuse. As a long-time tennis player, I knew immediately what to do and I captured the ball in almost all the pictures. The editor was impressed and he hired me. That was the beginning of my professional career and I haven’t stopped working since.

(continued) In 1989, after 10 years of freelancing, I established Reporters, a photo agency, with two other photographers. Within a few years, it grew from 3 to more than 25 people doing all types of photography. Around 2000, business was getting harder due to the internet and the rise of digital cameras. While both were great advancements, competition became tougher and more diverse, not only from other agencies but now almost anyone could sell, or try to sell, pictures. Prices dropped. This revolution affected magazines and newspapers as well and the money suddenly disappeared. Magazines no longer offered assignments or guarantees and we were forced to explore other sources of revenue like corporate communications and video. In 2012, I sold my shares in order to travel the world and shoot personal projects focusing on social issues and human interest stories. I have been a professional photographer for 45 years. Technically, I am retired (67) but still working.

(continued) In 1989, after 10 years of freelancing, I established Reporters, a photo agency, with two other photographers. Within a few years, it grew from 3 to more than 25 people doing all types of photography. Around 2000, business was getting harder due to the internet and the rise of digital cameras. While both were great advancements, competition became tougher and more diverse, not only from other agencies but now almost anyone could sell, or try to sell, pictures. Prices dropped. This revolution affected magazines and newspapers as well and the money suddenly disappeared. Magazines no longer offered assignments or guarantees and we were forced to explore other sources of revenue like corporate communications and video. In 2012, I sold my shares in order to travel the world and shoot personal projects focusing on social issues and human interest stories. I have been a professional photographer for 45 years. Technically, I am retired (67) but still working.

You capture really interesting subjects. How do you find your subject matter?

You capture really interesting subjects. How do you find your subject matter?

When I find something interesting, I do a print screen and file it on my computer. Years later, when I’m in a particular country, I have something to check or research that can eventually become a story, like the Grandma Divers series.

What kind of considerations do you take into account when creating a series?

I like to tell stories in a personal, visual way, through the sense of framing, the use of color or black and white… Shooting a series gives a better understanding of a story. In general, I am not a single-shot photographer. I think in series. Editing is key. You can tell one story or another by where you place the accent. Even here in a portrait series, the sequencing is important. I'm most interested in the in-depth reporting of stories relating to people and their environment. Various cultures, modes of living, rituals, and customs fascinate me. I strive to tell a story in 10–15 pictures, capturing the essence of an instant.

The Grandma Divers series is a compelling look at an aging group of women who free dive. What inspired you to capture their portraits?

The Grandma Divers series is a compelling look at an aging group of women who free dive. What inspired you to capture their portraits?

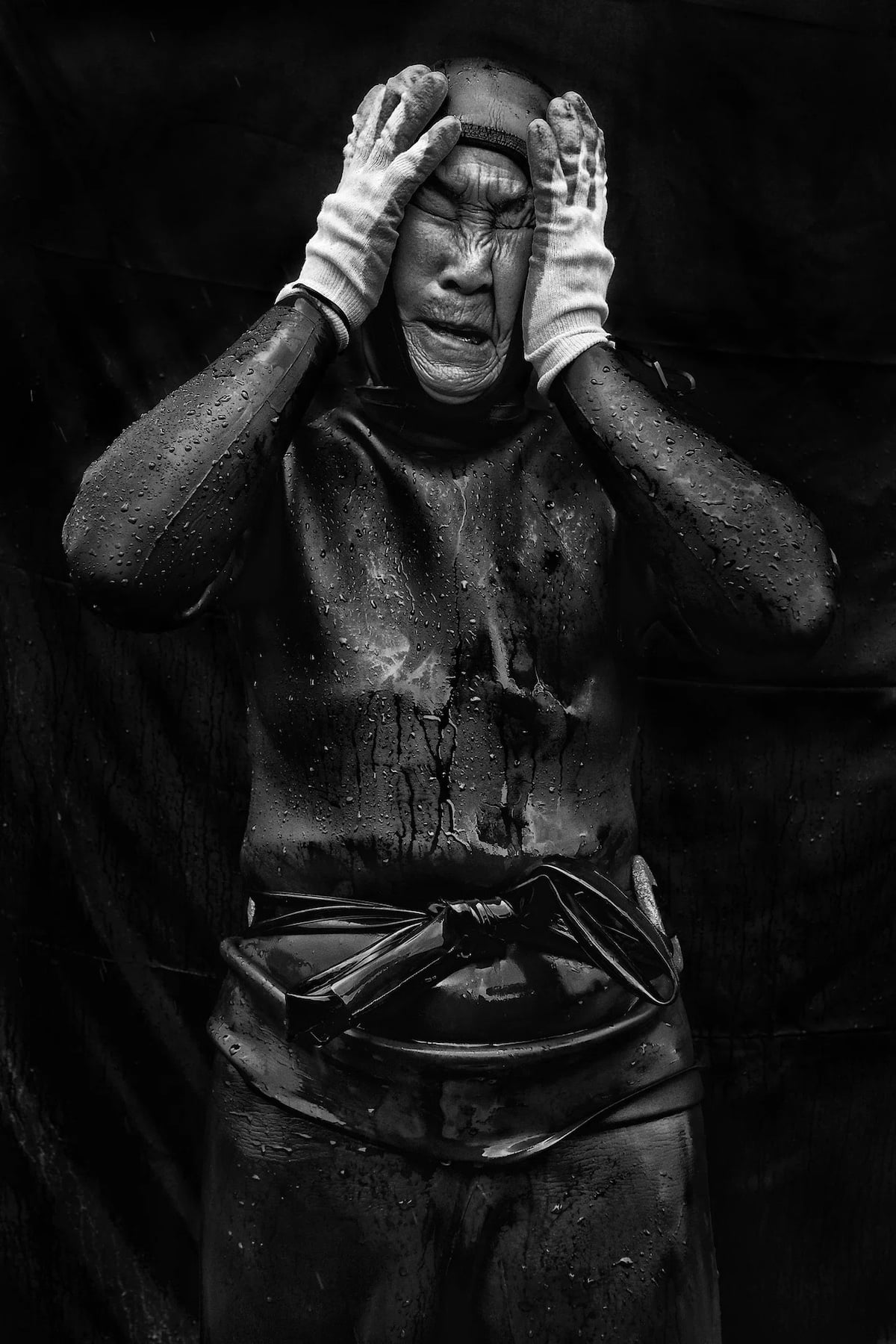

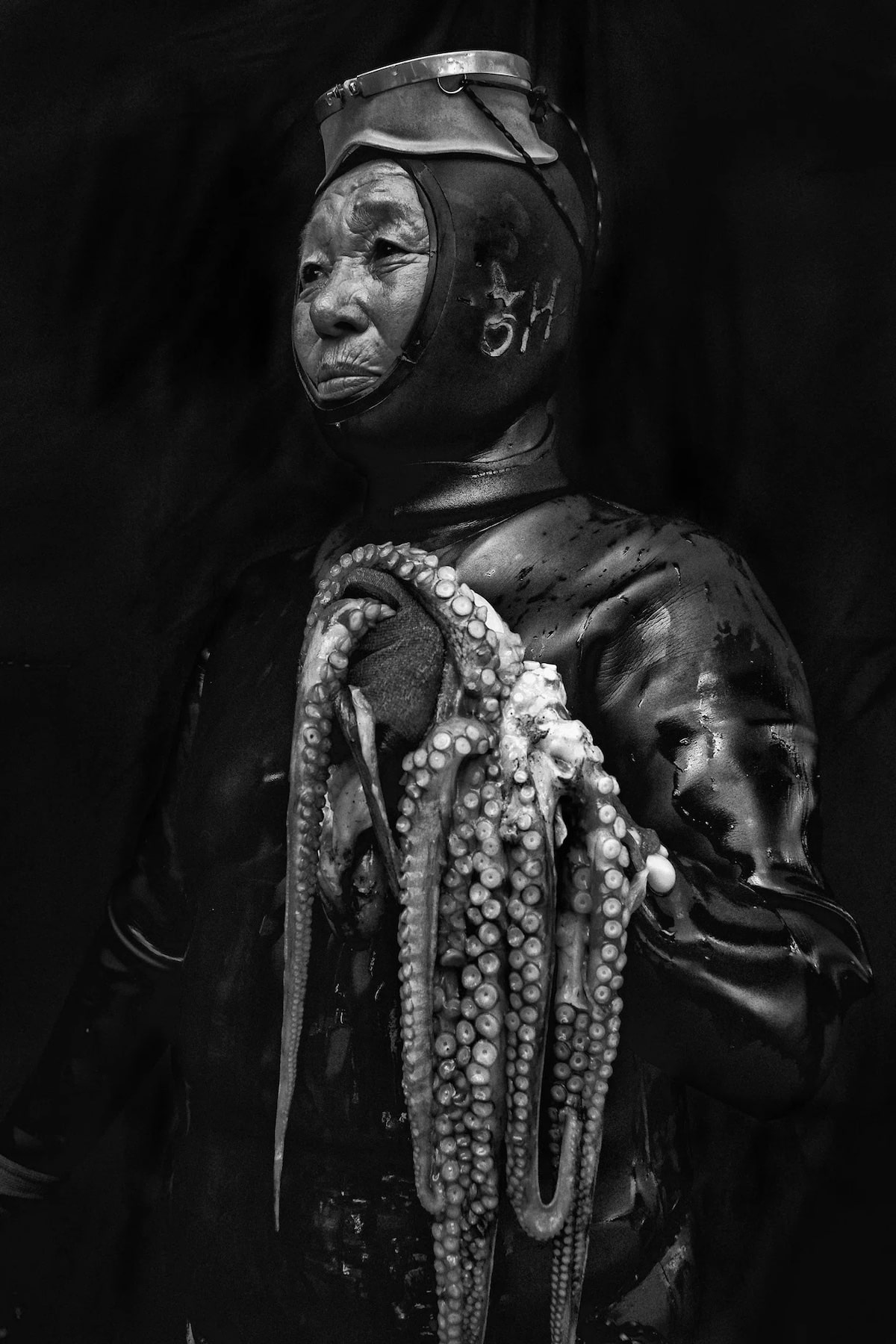

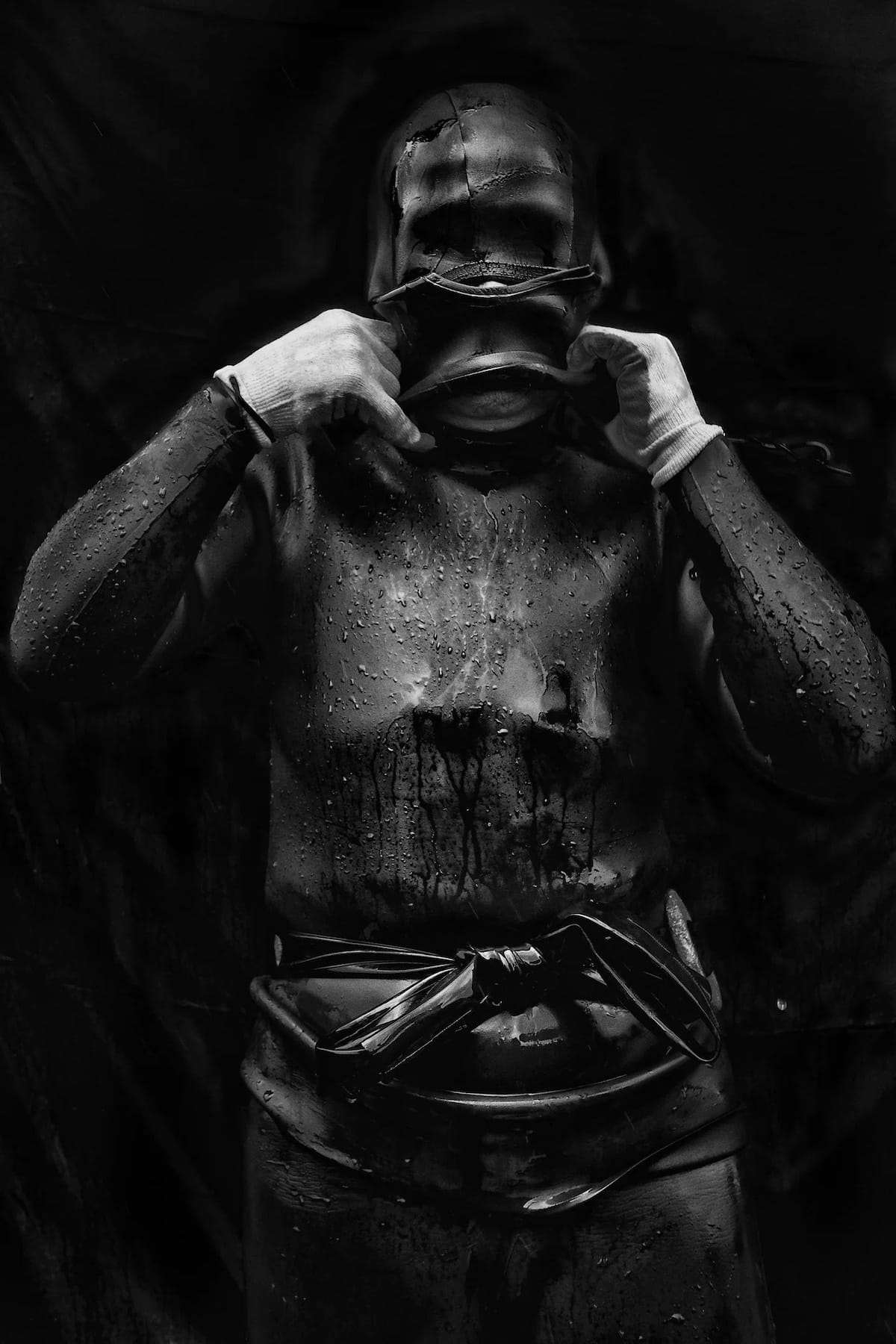

The first time I saw a diver coming out of the water, I was struck by her black wetsuit against a black background created by the basalt rock of Jeju (in South Korea). I immediately had the vision of the portraits I wanted (black on black, in black and white) and I was lucky to get them.

What was it like capturing the portraits of the women in Grandma Divers? Can you tell us a little more about them?

What was it like capturing the portraits of the women in Grandma Divers? Can you tell us a little more about them?

The overwhelming majority of Haenyeo are over the age of 60. Most of the ladies I shot were in their late 60s, early 70s. They are freediving to 10–20 meters, holding their breath for up to two full minutes! This occupation is highly regulated and organized by local fisheries. Divers adhere to strict rules regarding who can dive, when, where, what they can harvest, and allotted quantities. It is a difficult, risky lifestyle that is rapidly disappearing as young women choose to pursue other careers. Most of the divers told me they did not encourage their children to dive. Most of the women have been diving for 30–40 years or even longer. Their days are long. They can spend up to 7 hours a day in the cold water battling currents. Divers are separated by category and only the older, more experienced, divers can go further out and deeper. Today, they dive according to the tides and the weather and it is much more regulated than in the past.

Although freediving for seafood has existed for many centuries in Jeju, the practice was taken over by women in the 18th century, transforming the region into a semi-matriarchal society. Women were responsible for most of the household income, but numbers have dwindled since the 1970s as other opportunities (cultivating mandarin oranges and developing tourism) offer less arduous working conditions. There are still about 4,000 ladies who make a living by collecting delicacies from the sea. Today, they are celebrated as a national treasure and inscribed on the UNESCO list of Intangible Cultural Heritage, with a dedicated museum in Hado-ri, Gujwa-eup, on Jeju island.

(continued) The first time I went was in March and I saw them coming out of the water in a protected bay with a basalt (volcanic) rock in the distance. I shot with a telephoto lens and the background was totally black. With the wetsuit, that black-on-black was visually interesting. That was the start, but it was not the right season so I decided to go back in September. Then another problem appeared; a tropical storm and nobody was diving for one week. With only a few days left, I decided to buy a piece of black cloth and shoot the divers in front of it wherever I could. On one particular day, it was raining quite hard so the ladies were waiting to dive. I was lucky to be able to take advantage of that moment.

(continued) The first time I went was in March and I saw them coming out of the water in a protected bay with a basalt (volcanic) rock in the distance. I shot with a telephoto lens and the background was totally black. With the wetsuit, that black-on-black was visually interesting. That was the start, but it was not the right season so I decided to go back in September. Then another problem appeared; a tropical storm and nobody was diving for one week. With only a few days left, I decided to buy a piece of black cloth and shoot the divers in front of it wherever I could. On one particular day, it was raining quite hard so the ladies were waiting to dive. I was lucky to be able to take advantage of that moment.

Can you take us through your stylistic choices?

Can you take us through your stylistic choices?

As I said, I had the vision of the portraits I wanted (black, because of the color of their neoprene suit, on black in black and white). I attached the black backdrop with ropes and rocks to the side of one of their diving houses (a small structure made of volcanic rock) because it was very windy. I chose a location that would remain shaded if there was a break in the clouds as I did not want any sun in the pictures. I used a wide-angle lens to go close with a more dramatic effect, and I used low-angle shots to make the women appear stronger in the frame. The grey light was perfect to set the mood for the pictures. When I finally had divers willing to be photographed and permission to hang my backdrop, it rained almost the whole day and I had to shoot holding an umbrella. The good news about the rain is that it gives a nice sheen to the neoprene suit.

(continued) These women wear their experiences on their (wrinkled) faces. Their lifestyle is difficult and dangerous, but it is what they have been doing their whole lives and they are proud of their traditions. The women were difficult to engage even though I had a local fixer who spoke Korean and their dialect. Many of them were indifferent. To keep them standing in front of the backdrop long enough to get the shots, I asked them to demonstrate their daily gestures of preparation and at the same time respond to questions about their lives. The idea was to keep them busy for a few minutes without just standing there. A few ladies simply refused to participate. It is the first time that people did not react enthusiastically to the pictures. I don’t really understand why as I had a young assistant who spoke their dialect and we did not make any cultural mistakes, and at the end of the shooting, we bought some of their seafood and ate it. I think they have too much pressure from locals (there are almost no Western tourists) who want to shoot selfies with them and at a certain point, it is too much. The work they do is really hard and most simply prefer to be left alone.

(continued) These women wear their experiences on their (wrinkled) faces. Their lifestyle is difficult and dangerous, but it is what they have been doing their whole lives and they are proud of their traditions. The women were difficult to engage even though I had a local fixer who spoke Korean and their dialect. Many of them were indifferent. To keep them standing in front of the backdrop long enough to get the shots, I asked them to demonstrate their daily gestures of preparation and at the same time respond to questions about their lives. The idea was to keep them busy for a few minutes without just standing there. A few ladies simply refused to participate. It is the first time that people did not react enthusiastically to the pictures. I don’t really understand why as I had a young assistant who spoke their dialect and we did not make any cultural mistakes, and at the end of the shooting, we bought some of their seafood and ate it. I think they have too much pressure from locals (there are almost no Western tourists) who want to shoot selfies with them and at a certain point, it is too much. The work they do is really hard and most simply prefer to be left alone.

In the end, I was able to follow my stylistic choices; black on black with a focus on the texture. I wanted the pictures to have the same look and feel while depicting different aspects of their life.

When you photograph groups like Grandma Divers, how do you view your role as a photographer? What are your concerns as you work?

When you photograph groups like Grandma Divers, how do you view your role as a photographer? What are your concerns as you work?

I try to show various cultures and lifestyles; maybe show something you are not aware of.

Unfortunately, I did not really enjoy shooting this series as the women were not very cooperative despite my best efforts to work quickly and disturb their routine as little as possible. But Grandma Divers seems to be a popular series. Probably the right combination of drama, aesthetics, age, and harsh weather. It is the magic of photography.

What's on the horizon for you? Anything exciting you can tell us about?

A few years ago, I shot a story called Saving Orangutans which won two World Press and one POYI. I just came back from Indonesia (Sumatra and Borneo) where I spent 2 months completing that story with pictures illustrating the numerous environmental issues contributing to the destruction of their habitat.

Alain Schroeder: Website | Instagram

My Modern Met granted permission to feature photos by Alain Schroeder.

Related Articles:

The History of Photojournalism. How Photography Changed the Way We Receive News.

Rare Glass Octopus Is Captured on Video by Deep-Diving Researchers

Grandma’s Superhero Therapy

READ: Photographer Captures Portraits of ‘Grandma Divers’ Who Free Dive Deep Into the Sea [Interview]

0 Commentaires