Photojournalist Turned Nurse Pulls Back the Curtain on Hospital Life During COVID-19 [Interview]

“Don't suffer like me, get the vaccine immediately, it's not only protecting yourself, its protecting people like me”- Joel Croxton. Croxton was fully vaccinated but the virus took his life on September 14th due to his weakened immune system. Here, he prays with a hospital chaplain over an iPad held by his nurse Jessie Ramirez (left). His wife Sandra Croxton and son Mark Croxton hold his hands. (Alan Hawes, RN/MUSC)

Alan Hawes works as a registered nurse at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) in Charleston, but he comes with an interesting background. For more than 20 years, he worked as a photojournalist; and now he's using those skills to help pull back the curtain of what happens in the hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic. With the blessing of the hospital, as well as the patients and their loved ones, Hawes has been able to take a series of moving photos.

The images clearly show the raw emotion that circulates the hospital. From the nurses who must make heartbreaking phone calls to the patients who are struggling to survive, Hawes' photos pull no punches.

“Hospital leadership is incredibly supportive of Hawes sharing his photographs with the public,” Public Affairs and Media Relations Manager Carter Coyle tells My Modern Met. “His images showcase the harsh reality of COVID-19, and it is a privilege for Hawes to represent MUSC to local and national audiences. We hope his photo stories offer a glimpse at the heartache and heroism underway in our ICU right now. As hospitalizations from the Omicron variant continue, Hawes is continuing his photography work with the consent of his patients and supervisors.”

My Modern Met had the privilege to speak with Hawes during a break from his busy schedule. Covering everything from what led to his career change to what he hopes the public will learn from his work, this is an exclusive interview that cannot be missed.

Alan Hawes, RN

What pushed you to transition your career from photojournalism to nursing?

I had been a photojournalist for more than 20 years and the newspaper business was having great financial difficulties in 2008. Large layoffs at other newspapers—and it just got me thinking that if I ever wanted to have a second career, this would be the time. I love photojournalism and it will always be part of who I am, so this was a difficult decision. On many of my photo assignments, I would observe medics, nurses, respiratory therapists, and doctors working as a team with people in need and noticed that they had the same passion for their careers I did. I was an observer, and they were doers. I wanted to be a doer. Both careers can make a positive difference in the world and that is the standard I have for the careers I choose. I was 39 at the time and didn’t think I could continue having a secure career in photography for another 25.

Tala'Shea Foster holds an iPad as she visits with her newborn son Ta'myus Coffey via Facetime while she was recovering from COVID at MUSC. Ta'myus was born via an emergency cesarian section because Foster's COVID was so severe. She spent weeks near death on a ventilator in the ICU, eventually ending up with a temporary tracheostomy and a healthy baby boy who she hadn't held yet. She said she didn't know the vaccine was available to pregnant women. (Alan Hawes, RN/MUSC)

When did you realize that you could use your creative skills during the pandemic to help educate the public?

I knew before it even started in the U.S. I watched the news of coronavirus brewing in China and knew that I would be right in the middle of one of the biggest news stories of my lifetime. I work in an ICU that specializes in pulmonary medicine at the largest hospital in the state of South Carolina. We get the sickest of the sick. I read every study I could from China to the point where people were ribbing me that I was obsessed with COVID. The journalist in me was really pumped-up, but I knew I couldn’t photograph or report anything I was going to see due to patient confidentiality laws.

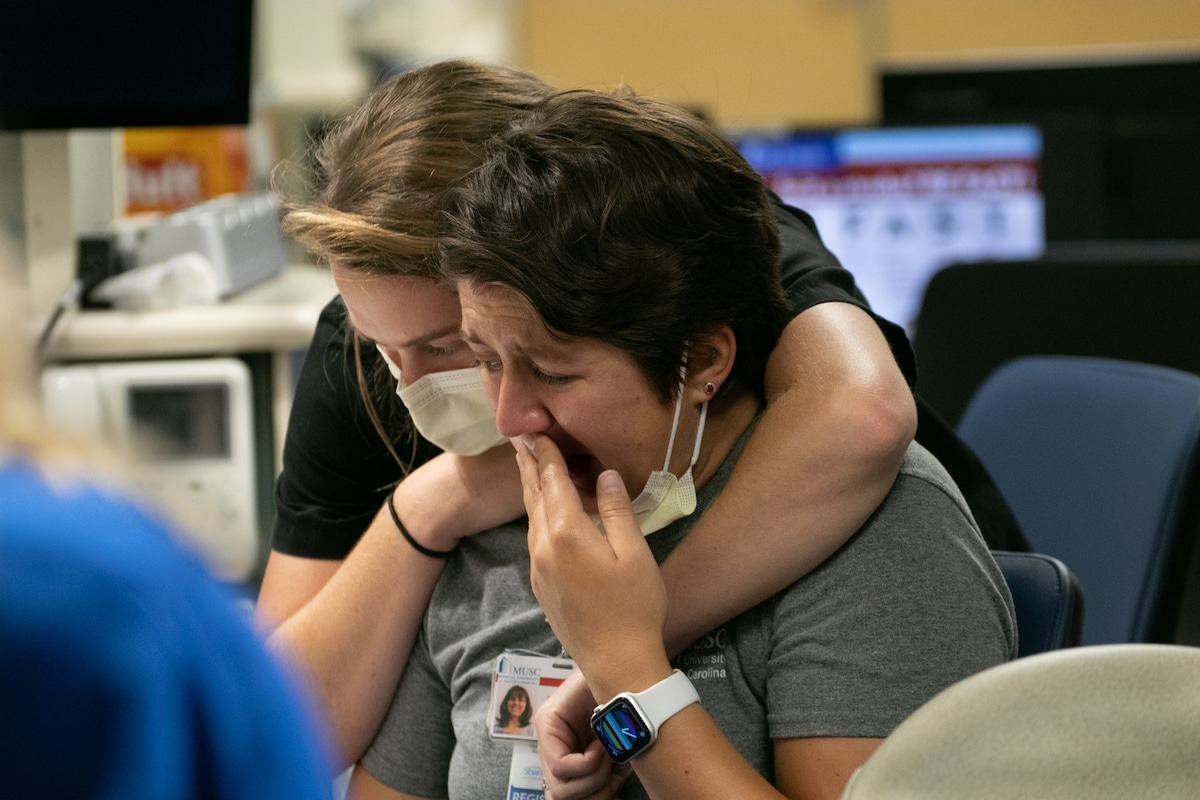

After completing a phone call to a patient's wife, telling her she needs to come to the hospital because her husband is actively dying, MICU nurse Andrea Crain cries at the nurse's station as patient care technician Kelly Burchette comforts her. “Everybody is dying and it just makes me so sad,” she said. (Alan Hawes, RN/MUSC)

How did (and do) patients and staff respond to your work?

I was surprised at how much the staff was supportive and encouraging me with the project once I got the official approvals. When I was a newspaper photographer in the hospital, I would always have someone say “You can’t have that camera in here!” But I now have many people per day stop me and thank me for helping to lift the veil on the stories going on in these buildings. Staff seems to really understand the power that these photos have. I want to fight misinformation with shared visual experiences. As far as patients and families, I have gotten very positive feedback from several patients and their families. The wife of Mr. Croxton told me that he would be proud to be such a prominent figure in this project, even though the photo of her husband in his last days was difficult to look at. The message is one that he was adamant in advocating for vaccinations to protect the individual and those they come in contact with. He was fully vaccinated and boosted, yet still died from COVID (he obviously caught from someone else) due to his weakened immune system.

Mary Moore holds the hand of her unvaccinated fiancé Steven Lavendar as his mother Tabitha Jones comforts him while he recovers from COVID with the assistance of a tracheostomy and a ventilator in the ICU. Lavendar spent weeks isolated in the specialized unit on a ventilator until he was no longer contagious and extubated. He was moved to another unit where he could have visitors. Lavender was unable to talk due to his tracheostomy but his fiance' said he said he thought he was “too busy” to get the vaccine. (Alan Hawes, RN/MUSC)

Do you have a particular story or experience that you'd like to share to help the public understand why sharing these difficult moments is so important?

I had an unvaccinated 30-year-old patient who was transferred from another hospital who had survived for two months in that ICU without being intubated. When she got to us, her lungs were so damaged that she could not delay the intubation any longer. I had her for several days in a row and she was doing poorly and it looked grave for her. Her family did not want to let her go no matter what. She was maxed out on every drug and on the highest ventilator setting we could deliver until we hit the point where we could do no more. I told her mother and father that we were at the end of the rope. Her mother dropped to her hands and knees, wrapped her arms around my ankle, and begged me to “please, do something.” All I could do is sit on the floor with her, put my arm around her and let her cry. Her daughter died later that night.

A COVID patient who tried to fight off the virus at home while his wife was in MUSC ICU with the virus, rolls into the MICU after being intubated in the emergency room. (Alan Hawes, RN/MUSC)

What sort of feedback have you received from the images?

More than I ever imagined. I am not a huge user of social media, so it was truly surreal to see how many people have seen my work especially when it was shared so much on Facebook. Total strangers come up to me and tell me they saw the images and that they shared them. The hospital community I work in is large, with three major hospitals all within a few blocks of each other. I haven’t heard anything but appreciation for showing the public all the work and emotions that come along with COVID. I have read a few troll messages which I expect but I’ve been really overwhelmed at how well people understand, appreciate, and support the intent of the project.

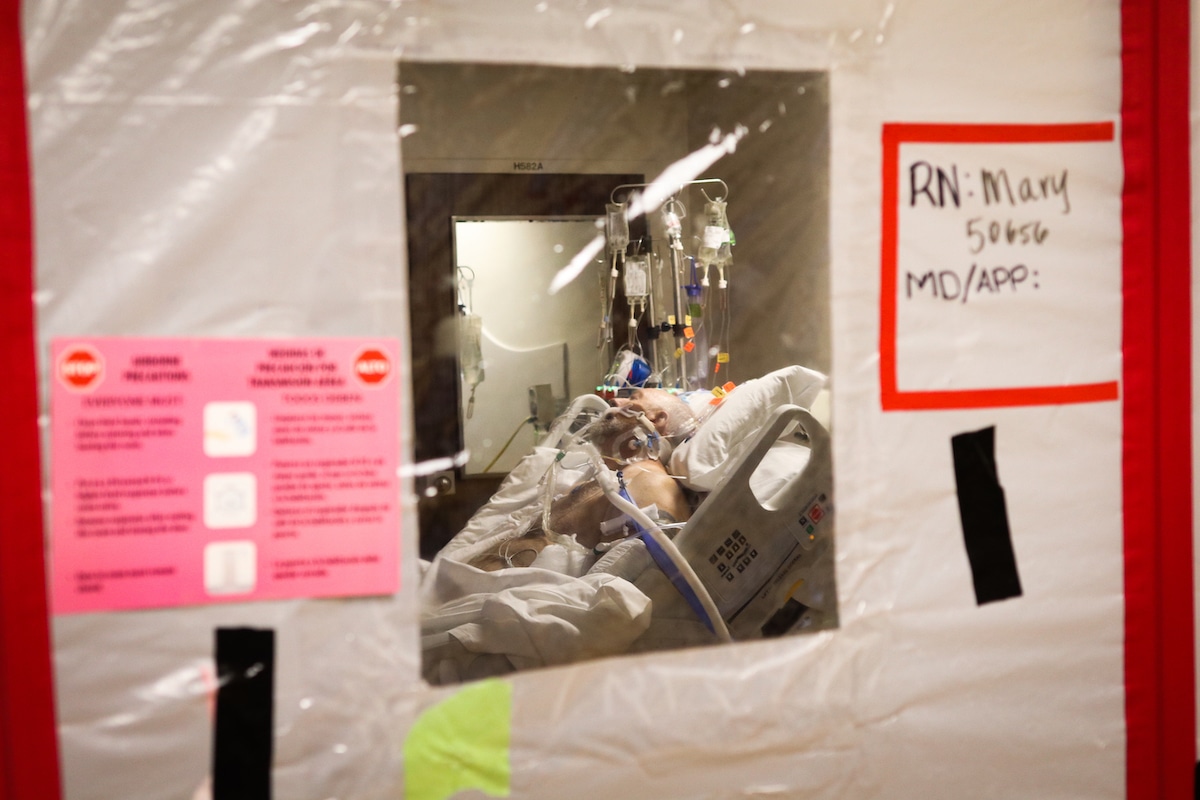

Lester Tumbleston lies in his ICU bed in a sealed room after being intubated for COVID-19. When asked about the vaccine before being intubated he said “I was just leary of it. Now I don't give a shit, I'm going to get it.” Tumbleston spent about two weeks on a ventilator. He was discharged from the hospital in early October. (Alan Hawes, RN/ MUSC)

What's the most challenging part of documenting this time in the hospital?

Finding the patients who are COVID positive and still clear-headed enough to be able to understand and sign photo consents. I prefer to have the subjects themselves sign the consent instead of a family member who has the legal consent signing power. It’s a goldilocks period of time, hospitalized but not too sick. I use all my contacts around the hospital to help me identify possible participants.

Dr. Denise Sese (left) discusses a patient's plan of care with ICU nurse Ericka Tollerson in the COVID ICU. (Alan Hawes, RN/MUSC)

What do you hope that the public takes away from your work?

Hospitals are overwhelmed. Understand that if you chose not to get vaccinated that your decision could cost someone else their life. If you spread it to a person who is vaccinated but has a weakened immune system, they can die. We have seen fully vaccinated people with weakened immunity die well before their time. Vaccinations keep most people out of the ICU. I can’t recall a single patient who was fully vaccinated and boosted with no other serious pre-existing conditions requiring intubation in the ICU. COVID patients are occupying ICU beds for weeks and months at a time. Nationwide, patients who need critical care beds for a heart attack or stroke or traumatic injury may have to wait in a busy ER for much longer than they should because there are so few or no ICU beds available.

Mary Moore holds the hand of her unvaccinated fiancé Steven Lavender as he recovers from COVID in the ICU. (Alan Hawes, RN/MUSC)

The COVID ICU is divided into two zones, yellow and red. Red sealed with negative pressure air to keep the airborne virus particles from leaving the room, but requires the staff to wear full PPE, including N-95 respirators and eye protection for most of their 12-hour shifts. (Alan Hawes, RN/MUSC)

Alan Hawes: Twitter

My Modern Met granted permission to feature photos by Alan Hawes/MUSC.

Related Articles:

A COVID-Friendly Embrace Wins the World Press Photo of the Year

Intimate Photo Goes Viral for Quietly Celebrating a Nurse Who Helps Deliver Babies

Nurse Who Saved Lives in California Fire Shares Images of Scorched Truck, Toyota Responds

670,000+ Flags Are Planted on the National Mall To Commemorate American Lives Lost to COVID-19

READ: Photojournalist Turned Nurse Pulls Back the Curtain on Hospital Life During COVID-19 [Interview]

0 Commentaires